Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

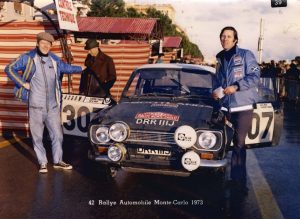

in Ford Escort RS1600 (DRR 111J)

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

On paper this year’s Alpine looked tough; on the map it looked impossible and it seemed it would take a good crew to go home in triumph carrying one of the coveted ‘Coupes des Alpes’.

The route was divided into three stages, or Etapes: Marseille to Cannes, Cannes to Chamonix and Chamonix to Monte Carlo. Each stage had 3 kinds of timed section: a liaison section, would be from, say, A to D and within this, from B to C might be a Selectif which would cover a difficult part of the route, timed separately and with crash hats worn. Instead of a Selectif there might be an Epreuve, a test to be covered as fast as possible. All rather complicated and I was glad that Pat Wright who was co-ing with me, would be having the timing job.

We arrived a few days before the start and before long rumours were rife about a nasty little col just north of Marseille. Accordingly, we went to investigate one night. It was 9 km long and we had 11 mins in which to do it. When we stopped the stop watch it was showing nearly 14 mins; not a very encouraging thought for when D-day arrived.

Scrutineering was held on the Sunday and Monday in Marseille and the weather, which hadn’t been too good, did its best and we wilted in blazing sunshine. My entry had been messed up from the start; we were running Group 1 in Class 5 but we had been accorded the number 15, amongst all the Coopers, and put down as Group 2. This resulted in slight chaos but finally we were allotted number 22. The rally plate for this number bore a French flag – more outcry as I refused to accept unless they replaced the tricolor with a Union Jack. After promises that this would be done we returned to our base at Cassis. By now the cars were in Parc Fermé so it was no good thinking about all the things we should have done. Instead, to try and relax was the best thing.

We were both glad when, late on Monday evening, we were allowed into the Parc Fermé; had a quick look to make sure that ‘Emma’ had no flat feet and soon we were leaving the glaring lights of the starting ramp, on our way to our first Selectif up the Sainte Baume. Directly behind us was a very fast Group 2 Alfa, very well driven by a racing driver, and this car would catch us on almost every long Selectif and Epreuve. Geoff Mabbs, running one of the Works very fast Group 2 Cortinas, would also pass.

I drove the Sainte Baume very badly and missed the bogey time by around a minute which didn’t make the idea of the dreaded Mimet Selectif (the one we had tried) very hopeful; however, strangely enough, I only missed this by 13 seconds.

Heading northwards and taking in various Selectifs and Liaison sections, some very difficult to even try to do in the time allowed because of stretched mileages, some not so hard, the hours of night flashed past and in the early dawn we had our first troubles. Emma showed every sign of acute petrol starvation; at times we almost came to a halt. Our nearest possible assistance was not until Bedoin where there was a Ford service crew and that was still 80 km away. Suddenly inspired, I switched over petrol tanks and this seemed to do the trick. At Bedoin we had our first Epreuve, a long climb of 21 km up Mt Ventoux; it was near the start of this that Pat Moss went out with engine trouble. The view from the top is always awe-inspiring and in the early morning the banks of cloud looked like long rows of pyramids; it was very beautiful.

As the day wore on it got hotter and hotter and on one of the few easier Liaison sections we did a crafty change into shorts – much cooler. Before the rally I had taken the precaution of making some old towels into seat covers and this stopped any sticking to the seats.

Many of the Selectifs were over small, twisting roads covered with treacherous, deep layers of loose chippings. It was wicked stuff to drive on as it made control of the car extremely difficult. By now the heat was really on: the sun blazed down, the tar melted and the liaison sections became very hard work as col after col came and went. In the middle of one of the Liaisons there was an Epreuve up and down the Col de la Cayolle and on the descent I had the first indication of brake fade; there was a little there but not enough for comfort and it slowed us down considerably. Unfortunately for us there was no let up in the cols and so little chance to let the brakes cool off and about 5 km short of the end of the Col de Valberg Selectif finishing at St Sauveur, coming on a rock tunnel, on an acute left-hander down the col, I put my foot on the brake and it went straight to the floor boards. There wasn’t much time to think; the mountain-side was on our left, a few trees and the usual drop on our right. I slammed Emma into 2nd, grabbed the hand brake and we proceeded to do the most perfect hand-brake turn, ending up facing the way we had just come! Pat jumped out to slow any other traffic while I shunted backwards and forwards to get Emma facing the right way. Miraculously we had hit nothing and just as the first Mini appeared we were ready to carry on, using only the hand brake. Mercifully, one of the Ford service cars was at St Sauveur and in 12 minutes they changed the pads (which were red hot and down to the rivets) and bled the brakes; we pushed on furiously but were 4 minutes late at the next control. Later in the day the exhaust tried to fall off but while Pat and I were tying this on the Ford team boys stopped and helped us. By the time we reached Cannes that evening we hadn’t eaten even a sandwich from the time we left Marseille, 24 hours earlier. We were both out on our feet but forced some food down then fell into bed and knew nothing more until 7.30 the next morning.

It was a depleted field that left Cannes; two of the Fords: Geoff Mabbs and Keinanen were out; of the females both Pat Moss and Anne Hall were out so now we could take advantage of the fantastic service that Fords had laid on. The first thing was getting the exhaust dealt with, which we did shortly after leaving Cannes, after the first Epreuve of the 2nd stage, a climb that I thoroughly enjoyed. Now we were getting the brakes bled just as frequently as needed; the Ford mechanics were marvellous and we even got some food! In comparison to the first stage the second one was certainly not as hard, though the pattern of the roads and loose ball-bearing surfaces still continued. Alas, even a reasonably easy Liaison section can prove to have its hazards, as we found out during the late afternoon.

By now the rest of the Ford team, Henry Taylor, David Seigle-Morris and Vic Elford had closed up with us. Generally they went past but on this particular stage none of us was hurrying and they were all behind us.

I don’t suppose we were doing more than 55 when suddenly there was a vast hole in the road, very deep and taking up nearly the full width. Frightened that I would break the suspension and springs if I went in, I tried to swerve. What happened then was just so quick that I really don’t know. We clouted a bank on the left and then Emma landed my side down. Pat was suspended above me but with her usual calm she asked if I was OK. I think I must have been slightly stunned for things are a bit hazy. The boys were with us in a flash; they were marvellous and so coping. They had Emma on her four wheels in no time. Henry spotted a farmer and yelled the magic word ‘tractor’ and ere long we were towed out. Henry then disappeared under the car and announced that the tie rod was bent but if we turned the track in a bit we could probably make it to the next control at Orpierre, 20 km away, where just beyond it was a Ford service car. The boys then had to push on and Pat, always superb especially in an emergency, together with the farmer, turned the track. Finally we decided that we had done enough to get us going.

Our farmer, who had been so helpful, refused to take anything for the trouble that we had put him to and so we pressed on. At the first right-hand bend there was the most awful bang and the steering wheel was snatched out of my hands. We both thought that the suspension must have collapsed but though we searched under the car nothing seemed to be falling apart. Then we saw the reason; the nearside wing which had been prised up to free the tyre had come down again. Out with the crow bar, but no matter how much I heaved and shoved nothing happened. This time another farmer had been standing watching; now he ambled over with two pieces of wood in his hand, went ‘tweak’ to the wing and the thing was free! If only he had come to our rescue right away we might ….. Ah well, he didn’t.

We pushed on, with Orpierre still around 10 km away when Geoff Mabbs flashed past us, in the opposite direction, looking for us. We couldn=t stop but I saw his brake lights going on and knew he would catch us in no time. And then our final undoing: there was a level crossing and it was closed! Geoff caught us here and told us everything was laid on at the service point. We waited for at least 3 or 4 minutes before the crossing lifted then with the tyres kicking up the most hideous din, we screeched our way into the control. We were late of course and by the time the boys had done a wonderful job of putting in a new tie rod and tracking up by eye, a further 25 minutes was added to our lateness. However, we pressed on. Unfortunately it was a difficult section in which to try and make up time and of course we now found ourselves up amongst all the hairy motor cars, like the Porches and the Healeys.

Our lateness didn’t increase during the rest of the stage to Chamonix but we had a nasty feeling we were 5 minutes outside the lateness allowance and this, alas, proved to be correct. It was rather heartbreaking. Determined, however, that we shouldn’t be out of the rally atmosphere we then followed the 3rd stage route, going to all the Liaison controls where the Ford service boys were, cooking for both the remaining team and the mechanics. This helped to restore our spirits a little. The bitter disappointment we felt can’t have been a fraction of that of David Seigle-Morris and Tony Nash who, with only 20 miles to go to the finish, leading the Touring Category and with a Coupe des Alpes almost in their hands, had it all snatched away; it was too cruel.

Any finisher deserved their laurels and it was marvellous to see Don and Erle Morley collecting yet another Coupe. What a superb team they are! What we did of the rally was very hard work but well worth while. Now poor Emma has gone for a ‘face lift’ – happily not a very serious one.

Tish Ozanne – 1964 Retyped by Pat Smith in 2001

Tales

Tales

Tales

Tales

The 1953 R.S.A.C. Scottish Coronation Rally

Tales

Tales